- Home

- James Edgecombe

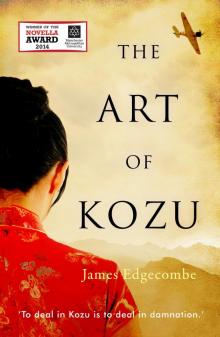

The Art of Kozu

The Art of Kozu Read online

James Edgecombe lives with his wife, Yuko, and their two children, Rintaro and Hinako, on the edge of Dartmoor National Park in southwest Devon. Having lived and taught in Hokkaido, Japan, he now teaches at Tavistock College, while also pursuing his PhD in creative writing at Plymouth University, where he is assistant editor of Short Fiction: the Visual Literary Journal. The tension between the visual and written arts has long fascinated him.

The Art of Kozu is a stunningly well-controlled piece of writing. Startlingly ambitious in its geographic and temporal range and in its subject matter, the writing makes remarkable use of voice and deployment of detail.

This work deals with art, death, aging, beauty, race, war and memory – and it’s a testament to the skill of its writer that after finishing it, I immediately read it again.

The novella was absolutely a stand-out piece, memorable, difficult, haunting and intelligent – never underestimating the reader and demonstrating with absolute clarity that a shorter work can have the thematic and emotional complexity of a full length novel.

Jenn Ashworth

Chair of the Judging Panel

THE ART OF KOZU

James Edgecombe

First published in Great Britain

and the United States of America in 2014

Sandstone Press Ltd

PO Box 5725

One High Street

Dingwall

Ross-shire

IV15 9WJ

Scotland.

www.sandstonepress.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Copyright © James Edgecombe 2014

The moral right of James Edgecombe to be recognised as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patent Act, 1988.

Editor: Robert Davidson

The Art of Kozu is the winner of the inaugural MMU Novella Award, a partnership between Manchester Metropolitan University’s Cheshire Campus, Sandstone Press and Time to Read, a forum of 22 library authorities in the North West of England.

The publisher acknowledges support from Creative Scotland towards publication of this volume.

ISBN: 978-1-910124-00-0

ISBNe: 978-1-910124-01-7

Cover design by Mark Ecob

Ebook by Iolaire Typesetting, Newtonmore

My thanks to Anthony Caleshu, Aya Louise McDonald, Gerard Donovan, Tom Vowler, Tom D’Evelyn, Madeleine Findlay; my mother and father, Carol and Colin Edgecombe; my children, Rintaro and Hinako, and, above all, Yuko Edgecombe.

To my children.

Contents

Preface

PART I – SELLING YUMIKO

PART II – BOY WITH NO BIG TOE

‘Messrs. O’Brien & Sons:

Gentlemen . . . At present and for some time past I see no reason why I should paint any pictures.

P.S. I will paint for money at any time. Any subject, any size.’

Winslow Homer (1836–1910)

YUICHIRO KOZU (1878–1953)

A RETROSPECTIVE

Born in 1878, the first son of military surgeon Roan Kozu (1855–1919), Yuichiro Kozu grew up in the port city of Hakodate, on the southern tip of the Kameda Peninsula, Hokkaido, Japan’s great island-wilderness and one of the country’s first international ports.{*} The city, however, was fortified; the site of the last stand of the Tokugawan rebels during the Boshin War (1868-1869) and an important outpost built by an empire ever weary of its neighbour, Russia. It is little wonder then, bearing these facts in mind, that Hakodate significantly influenced Kozu’s development as an artist: it symbolised for him what it meant to be ‘Japanese on the edge of the world,’ to belong to a nation looking outward, if guardedly so.

{*} The other ports were Yokohama (Honshu) and Nagasaki (Kyushu), which were opened up to trade with the West, after Commodore Perry forced the Tokugawa Shogunate to sign the Kanagawa Treaty in 1854, thus ending Sakoku, the Age of Isolation.

In 1906, he went to Paris. There, he refused to attend any of the ‘anesthetising academies’ crowded with his contemporaries, often quoting Monet’s instructions to Renoir, Sisley and Bazille: ‘We must leave this studio and our teacher. The air is unwholesome. Where is the sincerity?’ Having travelled half-way around the world, Kozu looked homeward, to the Japanese genre of the bijinga, those portraits of beautiful Japanese women that made him so famous in the 1920s (at the time he even outsold Picasso).

Kozu showed ambivalence towards the Japanese art world, staunchly dismissing a number of his countrymen as omu, or parrots. To him, his contemporaries seemed hell-bent on copying the methods and innovations of the west, without first allowing foreign ideas to percolate through and be absorbed by the Japanese sensibility. If a Japanese artist were to produce meaningful works, he said, they first had to plumb the depths of western oil paints, that gap between their realism and the uniqueness of the Japanese body. For Kozu, the artist’s ultimate goal was clear: to illuminate the Yamato spirit.

After the declaration of ‘Total War’ against China in 1937, and the reorganisation of the Japanese government’s official salons, Kozu became a war artist for the Imperial Army. For this reason his reputation suffered in the post-war period.

Only recently has academic interest in Kozu’s paintings revived. Such tentative explorations have borne interesting fruit. Prominent critic, Daichi Ando has asked that we, ‘look past the cruelty depicted in Kozu’s war art, to dig deep into the plight of those civilians trapped on the outlying islands of the empire, or the charred remains of our troops left on the field of battle in Mongolia, and to see the horror, made clear through Kozu’s canvases, for what it is: a lament.’{*} The artist’s sympathy and pity for those individuals he depicted is never in doubt.

{*} Sadly, few of these paintings exist today: most were destroyed in the firebombing of Tokyo, in March 1945.

Kozu died in Nice, France, in 1953.

Kasumi Takayanagi, 2014

Director of the Shin Midori Gallery, Ginza, Tokyo

PART I

SELLING YUMIKO

The Ginza, Tokyo, 1927

Ryunosuke Akutagawa, a friend of mine, and great writer according to his obituaries, committed suicide six months ago. I didn’t know him as a master of words – he was always so quiet. I never read anything he wrote. I only mention him because he hated any painting by Kozu. Often, we would argue over Kozu’s virtues as a human being, his vices as an artist of the real, for hours in the backroom after I had shut up for the night.

Since his early twenties, Akutagawa would come to my gallery to gaze at the oils on display. I saw a melancholy in him even then, when he was still a student. I thought that showing him the canvases I brought back from Europe, the monstrosities I bought straight from their Parisian artists, would lighten his mood. ‘See how ugly they are?’ I used to say to him, ‘you wouldn’t find anything as detestable as these on sale in the Mitsukoshi Department Store!’ I told him the reason I spent so much money on canvases I didn’t like, all portraits of some type or the other, was so that they could never be exhibited in Europe as visions of Japanese beauty.

A week before he murdered himself, Akutagawa came by the gallery and said, ‘I need to see the Kozu portrait!’ He claimed to have finally understood his lifelong melancholy that morning, after a night wandering around Honjo, where he saw a horse tethered to a cart beneath an iron bridge. The thick purple patches of shadow in the structure’s metalwork, around its rivets, across the horse’s back, around the cloud of steam puffed into the air by the beast, its great form little more than a silhouette in the morning twilight, struck him with the force of déjà vu. H

e knew the street before him, the bridge over his head, had walked that same route as a child. But that morning, it was fresh to his eyes, like a painting by one of his favourites, Van Gogh.

He told me he needed to know if the Kozu portrait could reproduce in him that same sadness. To him the Kozu was a step backward from the avant-garde, rendered by an artist who did not understand the expressive power of colour. To such an artist as Kozu, he would say, the muddy vulgarity of detail was prized above all else.

The reason I mention this is because your wife has shown a keen interest in the painting to which I am referring. That is why I must ask you whether she wants this painting for the right reasons. It has a history – a story I will tell you, just as I told my writer friend that morning when he came to the gallery, faint from the summer heat.

But it requires us to sit. At least for a little while. Here in this corner, where we can enjoy the morning light.

The cat in the foreground, its fur exquisitely rendered in sumi ink, stroke by stroke, hair by hair, may offer a brilliant contrast to the oils of the female figure, but it is only an adornment. Yuichiro Kozu was admittedly good at painting cats. But when it came to women, he was a genius. If I thought someone was to take ownership of this piece simply because they thought the cat charming, I would fear the ghost of Akutagawa for the rest of my days. Be assured, Yuichiro Kozu only included the beast to demonstrate his skill at rendering the texture of its fur. With the woman’s skin as clear as it is, pure like porcelain, her pubic hair covered by her hand, there was no other chance to bring to life the rough tactility of common objects. Even her hair is as smooth as the ribbon that fastens her braid.

Maybe the cat is as good a place to start as any. He was called Hugo. Yuichiro bought him in anticipation of his brother’s arrival in Paris. Jun Kozu hated cats. It was the summer of 1911, just before the theft of the Mona Lisa from the Louvre that August. Paris was already hot, I remember that much.

Jun’s hatred of cats can partially explain Yuichiro’s interest in portraiture from a young age. Let suffice, Jun had demonstrated to his older brother the benefits of shasei, of sketching from life, when they were little more than children. Jun was the hands on type, while Yuichiro, at first at least, was the visionary. Jun, long before he left Hakodate for medical school in Tokyo, used to perform his own anatomical studies on the neighbourhood strays. Yuichiro would join him, sketching the dissections, so that he came to see and understand the internal workings of pregnancy, death, how bones were held in place, how their nuances dictated the topography of what lay above, the musculature of the body, the contours of the skin. Just like the legend of the Heian artist Yoshide, who could paint people with lifelike precision, as long as he had seen them with his own eyes, Yuichiro could paint any cat, no matter how contorted its pose.

His ability to paint cats was a skill he put to good use in Paris. That was how he met the girl in the painting, his model, Yumiko, the young wife of one of his rivals. You see, Yuichiro loved women. When searching out new lovers on the Metro, he would drop his newspaper on the lap of some pretty girl and, as she picked it up, he would say, ‘What a coincidence, I see you read L’Anarchie, too! My name is Yuichiro Kozu. I paint cats.’

According to Yuichiro, the sight of Yumiko’s face amongst all those Parisians on the Line 6 train was like spotting a wild cherry in blossom on a mountainside. The symbolism of the radical newspaper in her hands must have meant little to her, caused no shock, or excitement because when he asked her what she was doing on the train, she replied that she liked to travel around Paris by Metro. She didn’t care if her husband owned an automobile. Yuichiro explained her love of trains like this: although she was raised in view of a great naval base in Tokyo, the Metro instilled within her such a sense of modernity that she felt compelled to use it on her daily trips north from Montparnasse to the Louvre, the more circuitous route the better.

Yuichiro asked her to model for him then and there, before all those people in the carriage. He enjoyed talking about such things, whether business or personal, in front of the foreigners in that brazen way, enjoying the freedom that comes when one knows his language is a room without windows. According to Yuichiro, she agreed without hesitation.

A month later, Yumiko laid herself over the Line 6 track at the Passy Station, the very same line she had been riding north on when Yuichiro introduced himself. I can remember the day after that incident. I was eating breakfast with both Yuichiro and Jun outside the Café Houdini in Montparnasse.

‘She leaned over the track, as the train moved off,’ Yuichiro said.

It seemed odd that the couple drinking coffee next to us could smile and hold hands as Yuichiro read the news aloud, translating the story straight from the paper into Japanese since Jun did not speak French.

‘Witnesses on the platform thought she was praying . . . The train made it half way across the Pont du Passy, before it stopped.’

He gave the paper to me so I could read the front page for myself, as if by my reading the words, the tragedy became real. I noticed immediately that he kept the fine details to himself, like how the flanges of the train’s wheels had cut through Yumiko’s shoulders like a guillotine. Her arms had dropped down beside the track, detached.

Yuichiro took a slither of tartine from the plate in the middle of our table. The red jam gleamed with what light ricocheted off the limestone walls rising above us. The café, located down a lane off the Carrefour Alésia, had only four tables outside its window. While Yuichiro preferred the grander cafés of the boulevards, the Café Rotonda, the Café Flora, Jun preferred to eat in such out of the way places. He said he liked the cooler air.

Jun listened to the news, chewing his fecelle with slow rotations of his jaw. He ate in silence most days, his eyes half shut as if concentrating on some tune in his head. Yuichiro was a different man altogether. Whenever eating breakfast at the Houdini, he would always look up at the limestone walls, to the strip of blue sky above. The spire of the Church Saint-Pierre-de-Montrouge burned white with the glare of the morning sun just beyond the lane’s entrance. The August heat would always creep down the walls, until the lane became stifling with a heat that lasted well into the night.

‘I wonder if there will be an investigation?’ Yuichiro said.

It is not a well-known fact that both Kozu brothers painted. What fewer know is that of the two brothers, Jun was the better technician. When he wasn’t at the small hospital his father had set up for him in Hakodate, after he had left military service, Jun would spend hours bent over a desk, sharpening pencils with an old fruit knife and lining them up in order of use. Jun had been a surgeon for the Japanese Red Cross during the campaign against the Russians, but the quiet of the small practice was better suited to his temperament, or so he said. Six years had passed since he cut and sowed the meat of soldiers, who cried under his knife, more with the shame of living, of not falling into the honourable silence of the battlefield, than with the pain. As a young man, he had wanted to study cartography at the Tokyo Technical School of Art, but had turned to medicine, after the school was forced to close by the traditionalist revival of the ‘90s. If it wasn’t for the summons Yuichiro had sent him from Paris, Jun would have stayed put, listening to the wheezing lungs of the elderly and tending the broken bones of children.

What Yuichiro lacked in precision, he made up for in emotion, a trait that caused the Kozu family no end of embarrassment. Three years Jun’s senior, Yuichiro had fled Hakodate to live and paint in Paris, filled with ambition – the dream – to become a great painter – the greatest Japanese painter in Europe. That he had fled his father’s anger, after an incident with a fisherman’s daughter, was not talked about in the Kozu family, though Jun later told me the story with relish. As it was, Yuichiro’s responsibilities as eldest son meant little to him. Paris, city of art, philosophy, electric lights, was all that mattered.

But Yuichiro was well aware of his brother’s prowess and so, the week before Jun arrived

in Paris, Yuichiro unleashed a fresh rumour to infest the cafés and ateliers of Montparnasse. The word on the street was that a new Japanese face was to appear in the quarter. Not the face of a quiet mind with blank, nihilistic eyes, like so many of the other young Japanese artists in their dark suits, scribbling away in some academie or other, their fop teachers breeding into them an aesthetic the critics would then use to dismiss them as academicians. Such was their lot. It was no wonder I saw so many of them during the week, silent, brooding, pacing the corridors of the Louvre, instead of walking the streets outside. No. This new face would be crisscrossed with scars. A man, so the rumour went, who believed in the Anarchist maxim of ‘propaganda of action’ and wanted to extend its fingers over the throat of Art herself – Yuichiro had a penchant for hyperbole. Before Jun even stepped foot onto the limestone cobbles of the artists’ quarter, Yuichiro had transformed the young doctor into a legend, a name debated in the cafés, at the edge of wine glasses.

Though I only met Yumiko in the flesh a couple of times, I got to know her form intimately. You see, during the month before Jun’s arrival Yuichiro introduced me to his studies of the girl. It is true to say, I found her thinness repulsive.

Yuichiro had been seeing Yumiko behind her husband’s back for about three weeks when I met him for breakfast at the Café Houdini. This was our Monday routine, as Mondays were the only day of a week the Louvre closed its doors to the public, freeing Yuichiro from his studies of the great masters, if only for a day. Yuichiro ordered coffee for the two of us. I drank the black liquid as best I could. I would have drowned the bitter taste with milk, just as Yuichiro did, but that would have upset my stomach. Though I had lived in Paris for almost a year by that time and had successfully trained myself to drink red wine, even to enjoy its taste, coffee always gave me a tremendous headache.

The Art of Kozu

The Art of Kozu