- Home

- James Edgecombe

The Art of Kozu Page 3

The Art of Kozu Read online

Page 3

I was amazed. Not three days before, I had walked past that girl, as I had done countless times before, collecting my easel from the warden who manned the store cupboard in the Salon Carré and joined the other copyists studying the paintings therein. Yuichiro would often join me there, if he was not preparing for a sale. He would never take up a brush though, choosing to sit there instead, staring at the pictures, making his own mental etchings.

Though I had never painted De Vinci’s lady myself, I never dreamed that she would be lost. The sense of shock was palpable on the streets: each man that passed me seemed lost in his own newspaper. The cafés were abuzz with conjecture.

I hurried to the Houdini, to the gossip and theories of the regulars.

It was a beautiful evening, what I have since come to call a silver dusk. All those who have lived in Paris know such evenings, when the sun is low, cutting underneath the ceiling of summer storm clouds; light rebounds, down off the cumulus grey, down into the city, off its limestone and up again. The effect is magical. Every surface beyond the orange lamps of the café awning, is touched by mercury. The air has a thickness, like coal smoke, like that which drifts up from the tugboats on the Seine, the little ones whose funnels collapse down at the bridges. One would hope for rain at such moments. Not because the evening air was unpleasant, but because a thunderous downpour would leave the streets, the cobles, the trees, the fruit carved into the facades of buildings, shining. Such a café night, with the heavens fleshly opened and purple above, is the essence of Van Gogh’s Café under Gaslight. A night without any black.

Such was the night of the theft and my first encounter with Jun. (I told you I would get here). The wine was warm on my lips, when I noticed Yuichiro with a shorter man outside the café’s window. Both were dressed in formal evening wear. From the stranger’s rigid gait and black hair, I instantly knew him to be Japanese. I had no idea I was looking at the so-called anarchist painter of Montparnasse. I took my glass and walked out into the warm air to join them.

‘We were just discussing my painting of Madame Saiki,’ Yuichiro said by way of a greeting. I liked the way he did that in front of other Japanese men, foregoing formalities and talking to me like an artist of significance. Fournier, the Houdini’s ancient waiter, brought me a chair and I joined the table. It was as I sat down that I looked directly at the stranger’s face, a visage brutally scarred. Jun must have noticed a change in my demeanour, for I had only just sat down when he introduced himself so memorably, following up with, ‘I am fortunate . . . more so than others,’ and an explanation, punctuated by sips of tea, of how he had arrived in Paris the day before, after spending an entire week in Marseille. The voyage had not agreed with him.

Jun’s face was not an ‘etching hatched of white lines,’ as Yuichiro had put it, but a single shard of shrapnel had sculpted his flesh in the most fascinating way. Yuichiro told the story. Jun sat in silence. Apparently, the Russians had gunned for the aid station where Jun laboured under Mt. Taipo-shan, wounding him while he tended the wounds of others. It was a wide incision, cutting from beside the bridge of his nose down into his mouth, parting his top lip. I do not mean to be grotesque, to linger on a mark of valour, but whenever I try to picture Jun, I see his mouth, curtain-lipped. His teeth. Little else. He never smiled in my presence and yet, there they were, his golden incisors, on display for all to see.

Yuichiro went on to tell me about how, earlier that evening, Jun and he had gone to watch a live demonstration of a machine that could pierce the flesh without the need of a wound. The image it presented to the stunned audience was the perfect copy of the bones that lay underneath.

Something about Yuichiro’s words brought Jun back to life. ‘Have you seen the portrait he speaks incessantly of?’ he asked of me, his Japanese vernacular. I didn’t know whether he felt the normal formalities unneeded in that foreign land, or that my station as an artist, in the midst of building a career, was beneath him.

Believing he was talking of the stolen De Vinci, I told Jun I had seen the Mona Lisa on many occasions.

He cut me off with, ‘No, no, not that painting. I am talking about this portrait of a Japanese girl. It seems to have possessed him, he talks of it so often!’

I looked at the rim of my glass, said that I had not, though Yuichiro had shown me some of his charcoal studies for it. My exact words are lost to me, but I explained how I thought Yuichiro’s choice of setting, the busy Metro carriage, was inspired. To gaze upon a naked Japanese beauty amongst the bustle of commuters, was the manifestation of the city’s cosmopolitan allure. Yumiko would become a symbol of the body universal – that gift of the flesh erstwhile hidden beneath our decorations, the picturesque accessories of custom. I tried to make my voice as animated as possible, intense, without appearing vulgar.

Jun nodded, ‘You should see it I think. Maybe someone else can tell my brother what a fool he is.’

I begged Jun’s pardon, while Yuichiro ordered three brandies.

‘His picture,’ Jun continued, ‘this so-called masterpiece. I’ll admit the carriage is technically proficient, but the girl, that supposed Japanese girl? She is a monstrosity.’

‘Always the academician,’ Yuichiro said, turning his eyes, those cold, cold eyes, upon me. He had removed his glasses and sat there, leaning back, hands folded behind his head. The brandies arrived and Jun’s tea was tidied away.

Yuichiro said, ‘As I said before, you must consider the picture’s balance. It is wonderful, with her back arched over her legs, her ribs cutting across the centre frame as vertical lines. Must I explain this every time? All lines rise upward; her tones are light, the colour of her skin pink, warm. She is not deathly white, as our tradition would have her. She is maybe ill, but she knows she is alive; skin and bones, yes, but consumed by life, her own thoughts, her reflection hanging over the city passing by outside. I’ve not given her an outline either: nothing holds her together, down; her halo merges with the carriage!’

‘Pretty words,’ Jun said. ‘But words are the work of a Sunday painter. Not an artist.’

Yuichiro blew a cloud of smoke into the silver light of the lane. I watched it change colour as it rolled into the shadows and nothingness. ‘Of course you would say that, when, it is the idea brother – and not its execution – that matters.’

I was stunned, thrilled. Never had I heard my own countrymen so animated, and in a public place, too. I couldn’t help myself and blurted out, ‘What is it about Saiki’s wife that so offends your sensibilities, Kozu-sensei?’

‘Her face. Her body I do not care for,’ Jun began. ‘But her face . . . it is a blasphemy. We sit here in a city mourning the loss of one girl’s smile and my brother thinks he can replace it with one of his own.’

As though part of a play, at that moment a feminine voice addressed our table in French, ‘My friend and I were wondering whether we could join you.’

It was Yumiko! And she was not alone. On her arm was a man with a scraggy beard that matched the colour of his tweed suit. I knew him to look at – he was an Italian artist, a sculptor, rumoured to store his shit under his bed. He reeked of garlic sausage.

Yumiko said something about the great theft and how Montparnasse was the place to be on such a night.

Without asking permission, the Italian sat down beside me and addressed Jun, ‘You there, Jap, I know you.’ He was drunk.

Yuichiro smiled, refusing, or so it looked, to acknowledge Yumiko. ‘Monsieur, who could you possibly know here?’

‘Him,’ said the beast, pointing at Jun. ‘You’re that phantom Jap painter.’

Jun looked around the table, but it was left to me to translate the Italian’s accusation. Wiping his hands with a napkin, Jun went to take his leave, but Yuichiro stopped him, saying, ‘Let’s see what this fellow has to say about my idea. What impeccable timing Yumiko.’

Jun took a second look at the girl. ‘This is Yumiko?’ he asked, ‘I wouldn’t have recognized her. Not having seen that monstrosi

ty, at least.’

Yumiko bowed, her movements greased with insolence, ‘Sensei.’

The Italian called over to Fournier, demanding he bring a fresh bottle of wine. He would drink with us tonight. Yuichiro went to introduce himself, but was cut off. The Italian knew who the print-seller from the rue du l’Alboni was. He had no interest in Japanese prints, nor any other wares that Yuichiro wished to proffer. What interested him was Jun, what such a man with a face so scarred had to say about the nature of painting beautiful faces.

Jun did not respond immediately. I can still picture him there, nursing his glass, studying Yumiko, the fading daylight flashing over his gold teeth.

The wine arrived. It rained.

‘Well, sir,’ Jun said at last, ‘I believe that abstraction is tantamount to laziness. It is nothing new, the artwork of our nation is emptied of detail, is full of lies. Your great Leonardo knew that.’

I translated.

The Italian smiled and shook his mane, slapping Jun on the shoulder with a dirty hand. Jun studied the mark it left on the white silk of his scarf.

‘That is not very revolutionary! Yumiko has told me all about you, Phantom. She told me many things, indeed. She said you would be here tonight,’ he pointed to a small table beside the piano, the Houdini’s only piece of substantial future other than its counter, ‘we’ve been watching!’

‘And what has she told you?’ Yuichiro asked, enjoying the blooms he had obviously planted.

The Italian filled his glass, preparing for a story

as if it were his own. Wine pooled in his beard.

Over his shoulder he called out whether any person could tell him how to calculate the proportions of a figure study. A voice called back from the night and rain beyond the awning, ‘Seven times – the

body should be seven times the length of the head!’

The Italian stared hard at Jun, ‘Nearly. Isn’t that true my friend?’ His voice fell to a whisper, ‘A body, from crown to sole, is seven and a half times the length of the head. Vitruvius taught us that, didn’t he? Yumiko tells me that you put old Vitruvius to the test, Jap; that at you measured some decapitated Russian with his own head! Is that true?’

Jun leaned forward. ‘It was at the Battle of Taishan,’ he said, his tone even. ‘Vitruvius was quite astute in his calculations.’

Well, sir, I didn’t know what to do. I reshaped Jun’s words into French. I had heard Yuichiro boast of his brother’s unconventional methods before, but I never expected them to be true.

Jun then asked Yumiko how such a declaration made her feel. He couldn’t imagine he had caused her any offense, what with her husband’s notorious love of Russian dancers. Saiki’s works were full of them, he was told. Was it true that the famed Masahiro Saiki had never asked his own wife to model for him?

I watched Yumiko’s lips curl into a smile, which she made no attempt to cover with her hand. The expression in her eyes is impossible to describe – it was not quite angry, not quite blank, either.

Before she could retort, Jun exclaimed, ‘There it is! In this light it is so plain to see! That is what you failed to capture in your picture brother: that is the face of a Japanese woman. You have spent far too long in the Louvre; far too long seeing the world through white eyes. Look at her face. How can you not see it? I could demonstrate what I meant if I had a skull specimen with me!’

And so it was spoken. At some point, we moved inside the café. The Italian, filthily drunk, told us stories about his childhood in Livorno. Looking around, to see that the place was empty, he lowered his voice and asked, ‘Do you know why this place is called the Houdini?’

I made a quip about how my money always vanished after drinking there, to which Yumiko belched out a laugh, the likes of which I have never heard emitted from a lady since. Yuichiro lifted his head and patted me on the back, as if he had been awake all along. Jun did not laugh.

The Italian called over to Fournier. The old waiter obviously had a soft spot for the wild-headed sculptor because, after wiping his hands on his apron, he came over to us and uncorked a bottle of brandy. Before he could pour himself a drink, I took the bottle and performed the action for him, as is our custom.

‘Tell them about the Houdini’s magical powers,’ the Italian asked the waiter.

Now, sir, many nowadays think the café was named after that great illusionist, as a witty way to commemorate the manner in which he died, struck in the stomach as he was while being sketched by an art student the other year. Fournier made a great show of coming round front and locking the doors before he explained that the Houdini was called the Houdini because it shared the key ingredient of any great conjurer’s trick: it had a trap door. Or rather, an access shaft made and abandoned by the Inspectorate of the Mines. A person could enter in the small café, and disappear, maybe to reappear somewhere else.

‘And why should trap doors interest us?’ Jun asked me to enquire.

The Italian replied in Fournier’s stead, ‘The Empire of Death, my friend! There are catacombs beneath our feet, places where you can play with as many skulls as you like. I know: I’ve been there. And you’ve put me in the mood for adventure.’

He winked at Yumiko.

I have thought about the events that followed that call to the catacombs many times, to the extent that I am no longer sure of the accuracy of my memory, like a Chinese apprentice copying the work of his master. What I remember is Fournier leading us down into the kitchen, a windowless room, its darkness absolute, where he handed each of us a candle. Like a line of the pious, we received our flames in turn. There were some low tunnels after that (in which Yuichiro had to bend at his waist), two stone stair cases and cobwebs – thick miasmas that tugged at one’s hair like the sticky fingers of children. The subterranean coolness was a relief after the heat above.

When we came to a wider tunnel, Fournier announced that we had reached the catacombs, pointing to a rough black line that ran along the ceiling. If we were to become separated, he explained, we were to follow that lifeline to an exit. The Italian pushed through to the front of our expeditionary force, his candle’s flame reflecting off Jun’s teeth.

The absence of light makes it difficult to recount our passage. Candlelight on chiselled limestone; the closeness of our breath; feet scraping wet gravel: all evoked a sensation within one’s heart, not a picture to the eye. Every now and then, the echoes of our passage would widen around us, bounding off into the black, into tunnel mouths left to their mystery.

We came upon two black-painted columns, sometime later, a white obelisk design painted on each. The inscription on the transom they held aloft read: ‘Halt! This here is the empire of death.’

Genius confronted us on the other side of the doorway, a sight I cannot give shape to with my descriptions – I wonder if even Akutagawa could? Bones, tens of thousands of them, were stacked in piles jutting out from the cavern walls. Layer upon layer upon layer: their numbers meaningless. The macabre architecture was a marvel, its craftsmanship impressing itself upon one’s reason. But the art of it struck a deeper cord. Edging along the bone banks, candle at arm’s length, my face level with the crania crested dams, the hollows within them filling with light, I admired the strange, brutal patterns which came into view: a wheel of long bones, spokes crowned with skulls; a heart of skulls; an altar’s cross.

Beside me, the Italian took up a skull and, despite its missing teeth and jawbone, pretended to bite Yumiko’s shoulder with it. Yumiko giggled with delight. ‘It’s so light,’ she said, taking the white orb from his hands. Yuichiro made a quip in Japanese about its similarities with the pronounced forehead of an Italian. The sculptor kissed Yumiko’s hand as in response to those words he could not have understood, and took her into the next chamber. Yuichiro followed.

I returned to Jun, who was muttering to himself about how the meat and liquid gave a head its weight, his body a silhouette, hunched over the lip of stack. With his candle so close to the wall, his hands we

re lost in the mire of shadows. I enquired as politely as I could what it was he was doing, looking as he did into my eyes like some soothsayer, a sham Hamlet.

‘Looking for a mandible,’ he replied. ‘To make a complete human vertex. There are things I must prove to my brother.’

After hearing the story of how the doctor had used a Russian head as a measure, I decided to help Jun fulfil his bizarre quest, digging my hands into the mound of bones. I can still remember the sensation, the lightness, which brought to mind the shells of cicadas. I discarded sheath after sheath, each with the surface texture of rain-pitted limestone, in my search for the more substantial grit of teeth.

Yuichiro rejoined us. At that moment I noticed the absence of Yumiko and the sculptor’s giggling, which until then had reached us from the adjoining chamber through waves of echoes. Engaged as he was with his search, I thought Jun had no interest in Yumiko’s behaviour and was content for her to do as she pleased with the gaijin. Or so I thought, until, quite abruptly, he stood up straight, receding as it seemed into the darkness.

‘Do not trouble yourself,’ he whispered. ‘Do you think a fish knows that it is wet? It may know the sensation of the air when it jumps to catch a fly, but, in a flash, it is back underwater, dreaming about the world above.’

Yuichiro’s breathing slowed and he threw down a tibia with a chuckle. ‘You know,’ he said, ‘at last you say something that makes sense.’

At some point, Yuichiro said that we should give up the hunt for Jun’s trophy of a mandible and leave, adding, ‘Do you think Saiki will miss his beloved wife, if we leave her down here with all the other skeletons? You never know, she might feel at home down here.’

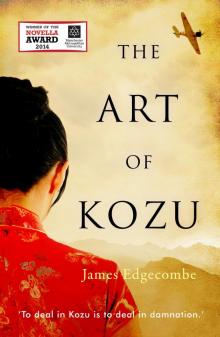

The Art of Kozu

The Art of Kozu