- Home

- James Edgecombe

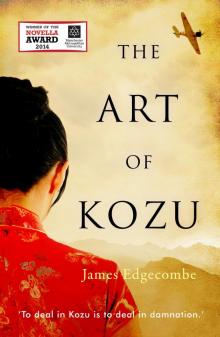

The Art of Kozu Page 5

The Art of Kozu Read online

Page 5

If you were to ask me where that earlier portrait was, that nude of Yumiko in which he saw her as she’d always wanted to see herself, I would ask your forgiveness, and say I don’t know. But, and I do not mean to speak out of turn, if you push me I will confide in you something I have thought for many years: that the original of the rebellious girl I met that summer in Paris still exists, not stored away somewhere, but painted over, just as Picasso did with so many of his earlier works. Just think, sir, the ghost of that wild girl could be haunting the very flesh that caresses the cat your wife finds so charming!

That was the story I told to Akutagawa. I always hoped he would write about it someday, given how much he detested Kozu’s portraits. But such speculation is by-the-by: I see your wife has come to collect you. I leave it up to you to decide whether or not to buy. The painting your wife so admires is one I have looked upon for, perhaps, too many years.

PART II

BOY WITH NO BIG TOE

The village of Nihongi, Nagano, 1947

In the moment before he laughed, the American bore an uncanny resemblance to the executioner from Toulouse-Lautrec’s lithograph, Au Pied de L’Échafaud. ‘Ah come on, Takayanagi,’ he said. ‘This little doozy’s kept me warm all the way out from Suzuka.’

His joke went like this:

‘A Japanese lieutenant-colonel walks into a French restaurant, the fancy kind with a maître‘d. Garcon! Garcon! Are you taking orders? the Jap calls outs. And the maître‘d replies: Oui monsieur, I am taking orders, but not as well as you.’

What could I say? As soon as I had caught sight of their jeep, its fresh layer of gloss the wrong shade of olive for our valley of burning leaves, I turned fleshless: a hungry ghost. I rubbed black mountain soil from my hands and the American coughed up another laugh, looking to his superior for support, a captain, whose uniform was so neat he could have been wearing an origami gown. The charcoal in our brazier popped but gave off little heat. The damp of the house seeped into me. How shabby the walls looked. How clean that uniform. My life was laid out in all its rudeness: the rotten tatami, the floorboards visible underneath, the fallen thatch wrinkling every surface.

The captain, tall and bored, was a Botticelli, from the master’s A Magis Adoratur. Do you know the painting? Have you seen him standing there, Botticelli himself, on the edge of the Medici family, those brutal patrons of Florence? I could see the captain was a man who liked to listen – listen and remember all the words he’s heard. A quiet man. His eyes a confrontation.

An apology slipped from my lips.

The captain waved his clipboard. There was a smile at some point. Enjoyment in the chase. He said, ‘The Old Man wants to clean up any remnants of the old wartime cliques. We’ve been tasked with confiscating any documentary campaign pieces that may have been removed from Tokyo after the surrender. They’re subversive. We are, after all, at peace.’

I called out to my wife for refreshments.

The captain refused to be distracted. ‘We were hoping to locate some works by a war artist connected to your grandfather’s gallery, a Yuichiro Kozu.’

I shrugged my shoulders, a gesture I thought my body had forgotten. ‘Kozu was friends with Soutine, when my grandfather represented the Lithuanian in Paris. That’s how I met him, once or twice, after he became famous. He died during the war, I read; Soutine that is. Not enough medicine. That is all I know about Kozu.’

The American looked at me as though I wore a Noh mask. His subordinate grew impatient, demanding I hand over any Kozus in my possession, anything I may have removed from Army Headquarters in Tokyo before the surrender, anything stored at my grandfather’s gallery. The house could easily be searched. My wife wouldn’t like that at all, he said.

I bowed. ‘The only artworks I own these days, gentlemen, I hang inside my head. As you can see, my wife and I are not very prosperous. Not anymore.’

‘Ah yes: the fire.’

‘The fire.’

At some point, my wife entered from the back and the captain instructed his man to mind his manners. Before each of us she delivered a steaming bowl of millet gruel, thickened with ground mountain yam, the vegetables I had just dug from the mountainside when the Americans’ jeep rumbled into our valley. I offered our guests a goza mat to sit on, a reedy husk our neighbours had once used to dry their vegetables on. We ate in silence.

But neither the soup nor the silence appeased them and soon the captain laid his chopsticks across the top of his bowl and said, mixing up my name, ‘Now then, Mr. Takayanagi-san, why don’t we have a little look in the woodshed?’ They spent the better part of an hour overturning everything in the small space while my wife and I looked on. The war is over, but suspicions continue. So, Doctor, I hope you understand that, even if I had the money you’re asking for, I would not buy your painting. There is no need to unwrap it. Believe me: I am glad you both survived the war. But you have been deemed useful in this new society of ours; your painting has not. To deal in Kozu is to deal in damnation. Yes, the war is over, but now the hunt is on for its criminals.

Let us put that aside for the moment. We have something in common and this should be celebrated, especially during this time of differences. Like the Americans, you were right to believe I once dealt in the great Kozu’s art. And even more so to believe that I knew more of him than what I told his would be captors. Will it surprise you to hear me say how once, when I was apprenticed to my grandfather’s offices in Paris, I accompanied him and Soutine on what Kozu had said would be a little ‘expedition’? They took me through the abattoirs around La Ruche. I can see them now. Un plaisir pour les yeux: Kozu in some peacock print shirt he had sewn himself; Soutine in that jacket of his, like a boiler-suit cut off at the waist, wearing his only pair of shoes.

Down an alley, its cobbles and walls shining with drizzle, we came across a knacker, his arms posed, wielding a lump hammer: a stroke away from putting an old Lipizzan horse to its passing. A hessian sack covered the beast’s face; its ears poked out through holes cut into the top. Holding onto the halter was the man’s handsome daughter, her eyes large and keen. Kozu – perhaps sensing my disquiet, perhaps aroused by the look on the girl’s face – approached the man. The knacker’s heavy apron was white: the horse was to be his first job of the day. With Kozu whispering in his ear, the old fellow nodded his thick head, given shape by a bushy moustache and cropped hair, and passed the hammer over to the artist’s hands. It took Kozu a single blow to split that horse’s skull. Soutine, I remember, was sorely disappointed because the carcass was too heavy, too cumbersome, to transport back to the commune.

Surely, you have heard the rumours? And so you know just how vigilant was their study of anatomy. I wonder if the extremity of an action such as this passed over me as much when I was a younger man as it does now upon recollection? But then again, wasn’t it Valery who said, ‘the skin is the deepest thing?’ Kozu bragged of the wonders those animals offered up. Raw textures of colour, he said: mother-of-pearl tendons, cut slack within an eviscerated rabbit; the flayed ox, split through the ribs: so many muddied shades of white, against a feast of rouge and brown. Soutine was the first to excel at recording these spectacles on his canvases. But Kozu advanced that art to another level altogether. And, yes, that is why I must tell you about your painting, Doctor. It deserves as much, as does Kozu himself. The moment Macarthur landed at Atsugi Airport, our greatest artist’s reputation crumbled. The Americans are looking to hang him and the new generation of artists have, like crows, hopped beyond the rubble of the past. Still, I have no doubt, Doctor, that, much like myself, you have the utmost respect for such adventurous types: the Chaim Soutines and Yuichiro Kozus of the world.

Does it surprise you, I wonder, that I know which work you have brought me from the parcel’s proportions alone? Let me describe for you the tableau: its Japanese soldier, centre left, little more than a silhouette is bursting into a darkened room. At his feet lies a white imperialist. Was this Frenchman cut down by

the soldier’s bayonet – that slash of gold, glittering in the doorway’s bar of honeyed light? We do not know. There is no blood on the blade. Just real gold leaf flashing over muted oils.

The night Kozu put his last touches to your painting, Doctor, Wagner was playing on the gramophone. The grand march from the German’s Tannhäuser – a favourite of Van Gogh. An hour past dusk and there Kozu was: studying his three models, pouring his soul into the forms he recast on his canvas. He closed his eyes often, cursed, remembering the scene the hour before, recalling the slant of a shadow on the soldier’s collar, his neck, beneath the ear, the quality of brightness along the shadow’s edge. How he wished he could freeze time, the sun’s quick descent. That is why he chose gold leaf for the blade. It shone with a light beyond the shades he mixed, his highlights. He did not like to paint from memory. If the essence of kokutai was to be evoked, ordinary light would not do. Kozu said as much himself. The body-national needed a touch of the divine. His soldier was a saviour. A liberator. And, while we contemplate his valiant pose, our eyes are drawn to the shadows, past the fine European furniture (edges and grooves picked out with great care – the texture of heavy curtains), to the figure in the bottom right-hand corner. Her skin is dark, eyes narrow, the girl, who, almost invisible in her black smock, is sitting on her knees, hands tied behind her back. What atrocity has been averted here? we ask.

A week. That is all it took Kozu to render what in times gone by some of us might have called a masterpiece. No other documentary artist could work so quickly. Not with such grace and dexterity. It is no wonder the Army sent Kozu everywhere to record their greatest moments: the storming of Singapore, Hong Kong. Some have said he flew in the back of a torpedo bomber at Pearl Harbour. In March of 1945, he was stationed in Saigon.

Doctor, you must have graduated in the last wave of students to leave medical school during the war. You look so young. Indulge me. There are some facts about your painting you may not be aware of, or were too busy to pay much attention to, given the calamities that befell Tokyo the last year of the war. I do not mean to give a history lesson, to patronise a bright fellow like yourself, but you may find it difficult to picture our military policy in Indochina, what with our decisiveness elsewhere. The key term the diplomats used was the ‘maintenance of tranquillity.’ The golden rule. Allow the French legislative organizations to remain, we thought, leave the police, economy, education, and all other domestic affairs under French control. We were engaged elsewhere and Paris had fallen. Why disrupt a vital rest stop; why poison your well, your breadbasket? Major General Sumita, I heard, advised his staff to conduct negotiations in a dedicatedly peaceful and friendly way. But it was an uneasy status quo. The Army said it would not support the independence movements in our area of operations, but it did – except of course, the Communists. Many of our native supporters were disposed of by the French Sûreté. We said we would not create bases for operations against southern China (the French feared igniting Chinese interest in their stricken colony), but again we did, especially after the declaration of war on America and Great Britain, when the army surrounded the French administrative headquarters and stated that General Decoux would facilitate our military presence in any way we saw fit. The French had no choice but to agree. The fear of losing their colony altogether was just too great. And as for the independence of the peoples of Indochina? Our diplomats thought that a matter of importance, but only as a future concern. Such a standoff, of course, did not last.

And, I can tell you Doctor, Kozu’s models were not Japanese, or French, as you may have heard elsewhere. All of them were Indochinese, even the gentleman on the floor, though he referred to himself as Chinese, despite having been raised under the same sulphorous sun. Ces messieurs, Doctor. Those gentlemen. That is how Kozu referred to your soldier and dead Frenchman. But is such a detail really worthy of note? After all, we all know Kozu’s reputation, his predilection for the grandiose. Just take the story about the Russian tank, the one he drove himself into the quietude of the garden of his Tokyo studio so he might render it in a dramatic scene of his own making.

One could be forgiven for thinking the soldier in your painting Japanese. How his face almost fits. He was called Trau, an ugly name for a beautiful youth. It meant ox and was given him by his grandmother to ward off evil spirits. To Kozu, he looked like the boy leading the elephant on the back of the 100 piastre note. Just talking to you Doctor, brings to mind a vision of Trau, standing there, in that corporal’s uniform , its white armband marked with a rising sun, imprinted with the character An – a military pun, meaning both security and An-nam, the middle kingdom of Vietnam. ‘Painting from life is the path away from melancholy.’ That is something the boy liked to say.

I realize I am ahead of myself. Permit me to slow down. Can I offer you the same bowl of millet and yams my wife served to the Americans? It is rough food, Doctor, especially for a man of your standing, though I do like to think the sweet flavour of the yam, its delicate orange colour, is imbued with a sort of rustic charm. After all, we have little else.

While we eat perhaps I should tell you about how I came to arrive at this point in my life – so ungrateful as I am for what I once, and I admit it, would have snapped your hand off for. No mere anecdote is required this time, but what I have heard the Americans call the ‘cold hard facts’. I came to the Cape St. Jacques in the rain: rough waters made pleasant by quiet skies. No American aircraft could prowl the coast, you see. By midnight, the stars and insects came out. The drive into Saigon was long. At The Institute of the Southern Ocean, the Japanese economic school on the Gallieni Boulevard, two military policemen were waiting for me. With no time to unpack my things, I was taken to the Majestic Hotel, a billet for the Japanese military.

Major Honma’s first words to me were, ‘Look at the legs of the British officers!’ I could see little of him, as I sat down at his rooftop table. His back was to the tropical sun. His shadow extended over the white table, the photograph of the English officers and their spindly legs. Limbs he was so bent on discussing. The Riviere de Saigon blazed, stretching both north and south, like wings sprouting from Honma’s thick shoulders. Curving out of sight in either direction, those waters gave the impression of forming an enormous circle, a River of Life, as envisioned in Buddhist scripture and the nihonga paintings of Yokoyama Taikan, a favourite of my grandfather’s. The sun was a hot coal. I thought, here was a man touched by the theatrical. Backlit as such, Honma could have been a vision of the Emperor himself, the faceless centre of our nation’s flag. The Hinomaru personified.

Honma insisted, ‘See?’

I did not see and nodded in agreement. Honma was a major in the Kenpeitai, Doctor. He could arrest anyone. Anyone at all. Even military officers up to four ranks above his own station. Imperial justice was his to interpret. I was not untouchable. Even today, many of his kind are unaccounted for by the British I hear, and the Americans, and the Dutch. All this trouble over a painting. The news clipping beneath his finger was from the Asahi Newspaper and showed General Percival on the day the British surrendered Singapore. I had seen the photograph before – had advised the cultural bureau to commission the documentary artist, Saburou Miyamoto to set the occasion in oils. But that was back in 1942. Things were not going so well.

‘How spindly their legs are,’ he said. ‘And their knees. They’re too thin. Those are weak joints, Takayanagi. I know about such things.’

‘The joints look frail.’

‘Soh, soh, They are frail. And spindly, like a spider crab’s: that is how Kozu described them when I showed him this same picture.’

‘Kozu is a genius.’

‘He is from Hokkaido. He must have grown up surrounded by the spiky bastards – the crabs that is, not the British. Though, I do question his attachment to the French. I’ve heard that you lived in France, too, Takayanagi.’

I told him I had.

Honma took a drag on his cigarette, which he held between his ring and baby finge

rs. An odd pose. An affectation. One I had seen perfected by a member of the Royal Family in the Philippines. He was a man who would never humble himself by supping on a bowl of millet soup. The cloud of blue smoke the major blew out over the stone railing beside him wheeled in the wet air above the rue Catinat, where it refused to dissipate.

At last he said, ‘You are on intimate terms with Yuichiro Kozu, Takayanagi, are you not?’

‘My grandfather represented his interests for many years in Tokyo, at the Midori Gallery on the Ginza. I met him in Paris. I wouldn’t say we know each other well.’

‘But you have been sent to Saigon to escort him back to the homeland. He and his military commissions. The Imperial Household itself has sent you.’

I was not to talk of such matters, but that meant nothing to a man like Honma. It was safer to bow, to nod, to say, ‘Yes, Major Honma.’

‘Let us understand each other, Takayanagi. Never would I dream of standing in the way of the Imperial Household, any more than I would with general headquarters. The Army sent Kozu here. Under my protection, he ventured north and painted the southern China front. The logistical preparations –to transport so valuable a consignment of national treasures back to Japan– are already made. Most of those paintings were completed in Hanoi. In fact, those paintings are at this moment on their way to the Cape St Jacques to be loaded onto the same hospital ship, which delivered you safely to my corner of the Empire. He tells me that all he has to do is finish a commission for Ambassador Yoshizawa.’

The Art of Kozu

The Art of Kozu