- Home

- James Edgecombe

The Art of Kozu Page 6

The Art of Kozu Read online

Page 6

Bowing, I mumbled my apologies. I thanked Honma for his loyal service to the Emperor.

‘Forgive me, but I have a humble request to ask of you Takayanagi. To my good fortune, Kozu has agreed to produce a painting for me. It is not to be anything spectacular; I can’t really call it a commission, my rank does not really permit such privileges. He assures me he will start it very soon. He is very specific about the conditions. A true man of detail.’

Honma, I realised, did not want Kozu to return, according to my schedule. I thought a moment and then told the major how I had also been tasked with preparing, for want of a better term, a safe house for any valuable artworks in the city. Those in need of protection should the French revolt, or the Americans invade by sea. I had a list of such pieces, prepared in advance by a cooperative French administer, no doubt one of Honma’s network. If the major could help me out in such matters, I would be most grateful. I assured him the works would take a little time to assemble – perhaps a week.

‘So we have an understanding, then,’ he said. ‘I am sure I have some information about the colonial residences in Laithiau that may interest you.’

Not a word that I am telling you embellishes my connection to Kozu, Doctor, and yet how removed from him I have come to be. In truth, those first few days in Saigon were a blur, but, though I seem to meander, there is good reason to do so. Be assured I will make all clear in time.

I finally met Kozu in person three days after Honma’s summons. At the time, we had not seen each other for fifteen years. I was called up from the crypt of the l’gélise Saint François-Xavier, the Roman Catholic church of Cholon, the Bastille of the Chinese City, and into the white heat of the street. A jade-coloured Adler limousine idled outside the gates, its rear engine augmented by some strange contraption for burning woodchips. Kozu was standing beside its open door, wearing something similar to a lieutenant-colonel’s uniform. He had made it himself. Replete with extra leather belts and pouches, pleats and creases, he could have been wearing a painting by Braque. Perspiration stained my shirt and trousers, a white so dark it was yellow.

I approached him and he stared at me, eyes roaming over my face, my body, as a glutinous man moves between the dishes of a large meal. ‘You!’ he called out. ‘So it is you they have sent to fetch me back to Tokyo – I was hoping for your grandfather.’

After apologizing for not contacting him earlier, I told the artist how busy I had been since my arrival.

‘Busy? What, in there?’ He looked at my escorts, two tired looking veterans, who seemed to be contemplating the stillness of a fly on the other side of the courtyard. I smiled as best I could, unwilling to risk his reaction, his flamboyant personality, with the knowledge that beneath our feet, in an second room dug into the crypt’s lowest vault by a team of British prisoners, were stored canvases by the likes of Courbet, Matisse, Seurat, Carot. He did not pursue the issue.

‘You must come by my studio, Takayanagi-kun.’ He smiled. ‘If you are anything like your grandfather, you will enjoy a little adventure. I’ll wait for you on the corner of the rue des Marins.’

At three o’clock, I found his café. From underneath his cap, the artist pretended to snore, wake with a start, only to declare with a flourish, ‘I have sent the car away.’ A native waitress laughed at his antics, until she caught my expression. ‘A walk will do you good. It is not healthy to spend so much time down a crypt. Believe me, I know.’

Doctor, the walk was a marvel in itself. I had only travelled by car between my lodgings at the economic school, the church and various houses in the French Quarter, where I gained entry with help from Honma’s men. The major had insisted I not wander about. The Saigon Sûreté still policed the city.

Now, on foot, those strange streets came alive, their shabbiness worthy of Van Gogh’s heavy brush strokes, the colours of lime, coriander, frangipani. Frying pork skin, mixed with brown sugar and garlic. Under the shade of kapok trees, invisible smoke dyed the air. Women ground peanuts. Everywhere locals in black smocks watched us through averted eyes. If we came close to them, they bowed, no doubt in supplication to Kozu’s uniform. Only in our wake, did their voices sing out again, like birds settling after a fright.

We crossed the Arroyo Chinois and minutes later the Canal dedoublement, where I watched the sunlight flash across brown water, slithers of space caught between brown boats, poled by brown skinned natives. To me, the canals looked to be full of flotsam, the debris of some great typhoon, which had flooded the city’s busiest boulevards with stinking water.

Dusk dropped over the Chinese City. Blackout regulations kept the canal and its warehouses in darkness. We made slow progress along the route de Binh Bông, passing peasants heading back to their hamlets beyond the city limits. In their black pyjamas and against the white glow of the road’s dirt, they resembled spent matchsticks. To our left the paddy fields and marshes of the countryside washed up against the dyke, a humming thundercloud of bullfrog songs.

We arrived at Kozu’s villa in the dark. The artist pulled on a bell-chain and turned to me.

‘I could not tell you earlier, but I am not ready to return to Japan, not yet,’ he said.

Caught off guard, I spluttered something about the Americans. The fear of an invasion. The likelihood of French treachery.

‘No. Not yet.’

‘Is this because of Major Honma?’ I asked.

‘What’s Honma to do with anything?’

The door opened and an old maid let us in. Her face, I saw in the light of the taper-lamp she handed Kozu, was marked by some childhood disease. She greeted the artist, as though he were the house’s returning patriarch.

Electricity was rationed. The studio of a war artist, no matter his reputation, did not warrant special attention. Darkness welled in the house, its high-ceilings, and somewhere within that vacuum, a gramophone played a waltz. I followed Kozu and his lamp. At his ease, the artist led me through the hall, past a tiger skin, then a pair of enormous elephant tusks set in a bronze stand. The flame moved like a cat’s eye, across the burnished surface. The walls of the corridors were painted with writhing vines, a queer throwback to Art Nouveau, which extended as far as the ironwork of the spiral staircase we ascended.

We came to the door of a large bedroom. Inside, a veranda was visible through a set of tall bay windows. The same moonlight that cut its iron fencing into parallel streaks broke into a thousand fist-sized diamonds, scattering across the boards of the room’s floor. The latticed panels of the house’s outer wall were a sign the architect had surrendered to the climate at least once. The diamonds illuminated a large canvas laid flat on the floor: a true Asian, Kozu had long since abandoned the easel. The strange light created the illusion that the canvas was hovering. Within that frame I could make out little actual painting, just a large empty space, like the vacuous mists of a silk scroll. Kozu asked that I wait in the doorway. By then, the gramophone ground out a cyclical white noise somewhere by the open window.

The artist crept around the edge of the room, lifted the needle from the record and drew the blackout curtains, all the time muttering under his breath. After that he lit various candles around the room using his lamp’s flame, his movements quick and practiced as if laying down strokes of paint. The details of the canvas consolidated, but there was not much to see, just a layer of burnt sienna under-paint. I stepped into the room and took a closer look. A figure, in rough outline, a graphite rifle held out before him, was charging into the blank, muddied space. A wispy set of lines picked out a doorway around him.

In short, it was your painting, Doctor; only, it wasn’t a painting then. Just a thatch of pencil hatchings.

And then I saw them: a man in uniform; next to him another, his face covered by a bed sheet. I rushed around the edge of the canvas, grabbing Kozu by the arm. The artist, leaning over a bed that had been pushed over into the corner of the room, shook off my hand with irritation and returned his attention to a third figure, a girl dressed in the

black pyjamas of a peasant. The girl roused and smiled at his touch, her teeth catching the lamplight. And what a beauty she was, Doctor. She rose from the bed, like a ghost, brushed the creases out of her simple clothing and ran her fingers through her long hair – a black mass that fell down to her waist, like a painting of a Heian courtesan.

‘This is Kieu,’ Kozu said. ‘She is the lady of the house.’ He gestured over his canvas to the two men lying on the floor. ‘That there is Petrus, her husband, under the sheet. The other –the boy– is her brother.’

‘You mean the soldier is a native?’

‘Un.’

My fright left me and was replaced with a deeper sense of fear. ‘He is impersonating an Imperial soldier! If Honma found out, he’d be executed.’

Kozu asked Kieu to bring us a drink (and so here I will pause, just briefly, to ask if you, Doctor, would you like another drink yourself. No? I don’t blame you. The story is always more compelling than a cup of wheat tea. Well, then I’ll continue). Kozu added that that we would wait for her on the balcony. With his boot, he nudged the boy in the soldier’s uniform and said in French, ‘Oi, my friend here wants to hang you.’

The figure groaned and reached for the gramophone needle, which Kozu took from his fingers. The soldier drifted back off to sleep.

‘This wretch, Takayanagi-kun, is my protégée: Trau.’ Kozu took a jug of water from the washstand and soaked the boy’s face.

The boy spluttered and got to his knees, shaking his head, eyes wide with confusion. His fists were clenched. In that uniform, its stitching loose, cotton scuffed, he was a vision of impudent rage, like one of the old timers I had seen marching back to Shanghai from Nanjing, his pain held at bay by amphetamines. He looked from Kozu to me, a Japanese stranger, and took a series of deep breaths to calm himself.

‘We thought you’d be back sooner, Yuichiro,’ the boy gasped. ‘When you didn’t come, we had a smoke to pass the time.’

Kozu nodded. ‘What about him?’ He motioned to the prostrate form on the floor.

‘You’d better not. Petrus was smoking your Golden Bats even before you left.’

The figure at our feet mumbled something in his native tongue: a series of disjunctive plucks on a koto string.

Trau’s legs shook but he managed to get to his feet. Kozu led us out behind the blackout curtain and onto the veranda. The heat was there, too, even in the white flashes of moonlight reaching up from the canal beneath us and moving across the walls. A pleasant heat. A tangible mass that absorbed me, as I eased down onto the stylish butterfly chair Kozu had pushed over for me. Its metal frame was wet. Trau lit a cigarette and exhaled smoke as sweet as incense, offering one to Kozu. The artist explained to the boy that I was an art dealer from Tokyo, the grandson of a legend. Not a military man.

‘March,’ Trau said, falling back into a chair of his own, the neck and shoulders of his khaki uniform still black with water. ‘This is the best time of year to stay in Cholon, M. Takayanagi. You chose a good time to visit. April will be here soon. The humidity will return. And the sun will lose its clarity. Every surface will dull.’

The girl returned. She poured out three drinks from a decanter and said something to Trau. He translated. The wine was made from tamarinds, he explained, a local brew to circumvent wartime restrictions. His sister was worried it might be too sweet for my liking. Kozu, I noticed, watched her every move. After she disappeared inside again, his eyes remained fixed on the edge of the blackout curtains. As if sensing my questions, the artist sipped from his glass and said, ‘Tell him Trau.’

The boy tapped ash from his cigarette and asked whether I was intimate with the works of Van Gogh. Of course, I said.

‘I am the Dutchman’s reincarnated soul,’ he said. Not a living a ghost, he insisted; he was not possessed. What moved within him was a force, an inextricable intuition, which held him in situ between East and West. Those were his words, Doctor. Like you, I almost laughed, only the boy’s sincerity kept me civil. Trau told me of how he had attended the Lycée Chasseloup-Laubat in Saigon, before his grand adventure north to study under Joseph Inguimberty at the Ecole Des Beaux-Arts in Hanoi. His stay proved both disastrous and fruitful. Director Inguimberty suffered, what Trau named ‘a crisis of line,’ and turned on the boy from the south, stating that colour was the better way to portray the tropical atmosphere. Trau agreed, in part, but could not abandon his expressive lines. They were as fundamental to him as fish sauce, a root of the Asian tradition. Van Gogh had understood the importance of outlines. Where the wild Dutchman had painted the fields around Arles, touched as he was by the aesthetics of the Japanese woodprint, Trau looked to paint in the other direction: an Oriental looking upon the paddy fields of his homeland with an eye to capture their essence in bright oils.

It was only to be expected that such an impressionable youth follow Kozu, the only Asian painter to make his name in Paris: a master of the real, when the avant-garde paraded their abstractionist rhetoric. Kozu had shown the world that Asians could pierce the look of the contingent world. That, for us, abstraction was nothing new. To the likes of Trau and Kozu, the very act of divorcing art from its mimetic function was a tyranny.

The story told, I emptied my third glass and poured myself another, by then feeling quite at home. ‘If only we had some absinthe.’ I said, quite outside of myself as I saluted the young corporal. ‘And a couple of 2 franc whores.’

The young Viet smiled his 100 piastre smile. ‘If only . . . But we do have Golden Bat cigarettes. Would you care for a smoke, M.Takayanagi?’

That night I learned about how Kozu came to be at the villa on the edge of the Chinese City, about how the master artist, on returning from a lecture he had given to the Anamese Royal Family in Hue, had come across the boy on the side of the road, where he stood, waist deep in mud, sketching a sleeping water buffalo in charcoal. When Kozu had quizzed the boy, he found out the youth had walked to the ancient capital and was heading back to Cholon. He had little more than ten piastres on him, much like Van Gogh had had when he walked out of Paris to Courrières and slept in a haystack, a hoar frost blanching the landscape around him. Apparently, on returning to Saigon, Trau had sent Kozu a portrait of the artist he had painted, an inversion of how Van Gogh introduced himself to Gauguin. Before you ask, Doctor, no; I never saw such a painting. Kozu had in turn, invited Trau to model for him, to take the role of the soldier in his commission for the ambassador.

The boy’s French was excellent, his manner patient. I took his sweet tasting cigarettes and listened to his explanation of how his-brother-in-law was a rice merchant, the son of a radical Chinese father who had come to Cholon to make his fortune. That was how, out of custom with the all the other Chinese who occupied the canal district, Petrus had been named after a famous Saigonese dignitary.

Trau had come to live with his sister and her husband, after he returned home from Hanoi to find that his town had become, what he called, ‘busy’ with Communist cadres. Before the war, the village had been markedly different. Most of its houses were built of brick and not thatch. One family owned a generator, another, a French bicycle. Trau was very proud of his paternal village. It was a fount of civilization, where cactus fences were a thing of the past; where Nice tiles covered the hard-earth floors. Still, the villagers attended their ancestor’s graves and grew their jackfruit trees on the outskirts, for fear of the ghosts the fruits attracted. The villagers were exceptionally filial people, he disclosed with a shy smile. Then came Kieu and Petrus’ marriage; the result of a defaulted loan.

We breakfasted in the garden next morning, rising in an hour of coolness after rain. The sky brightened quickly, but the sun took its time in reaching us, due the great height of the rice mill that stretched out from the mansion’s eastern walls. High over our heads, to the west, was the chimney of Petrus’ distillery. The villa, too, was impressive, a red-brick affair, more architecturally at ease on the rue de Recluse, under the shadow of the Eiffel Tower, than on the

edge of the Canal dedoublement. The mill and distillery were alive with voices, as was the canal itself. On its far side, we watched a group of POWs shift crates from a barge onto a truck, under the eye of a Korean soldier with a strong accent, a sight I had grown accustomed to in Shanghai and whilst working under the Catholic church in Cholon.

‘They blew up the prison camp last month,’ Kozu told me, ‘their own bombers. Can you believe that?’

But I was only half listening. The delights laid out on the table before us by the ugly maid amazed me more. Somehow Petrus had access to coffee and cow’s milk and other luxuries not even the French administrators could get their hands on. His wealth was truly formidable; the war could not erode it. Quite the opposite. With oil at a premium, Petrus was augmenting his fortune through the distillation of aviation fuel from his rice stocks and dismissed any mention of the famine in the north.

As we ate, Trau painted his ekphrastic dreams for my benefit. Lost amongst his own words, Doctor, he reminded me very much of my own grandfather, back at our gallery on the Ginza.

‘I intend the marriage of two shades of green,’ he said between bites of rice-flour-bread, ‘not mixed colours; not a single shade; but two antonymous colours, placed side by side on a canvas. The outcome will be a kind of magic. One could call it the mystic vibrations of kindred tones.’ Where Van Gogh obsessed over yellow, Trau loved green.

Kozu refused to eat, complaining that the opium-laced Golden Bat cigarettes had given him stomach cramps. He chose, instead, to walk up and down the edge of the canal, watching those prisoners, occasionally coming back to the table to pause and watch Trau’s sister, as she listened to her brother swear an oath that he would not rest from painting the rice fields and rubber plantations of his homeland, until he had succeeded in finding two such mates, had laid them down together as bedfellows, or better yet, as two tragic lovers in a tomb. The mutuality of their presence, he assured her and the whitening sky, would revive them both.

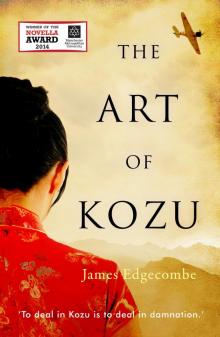

The Art of Kozu

The Art of Kozu