- Home

- James Edgecombe

The Art of Kozu Page 7

The Art of Kozu Read online

Page 7

In all honesty, I was lost for words most of the time. How was I to react to the young Viet’s manifesto? To derail the youngster’s ideals would have meant angering Kozu. That, I was not prepared to do. Still, I wanted to say to him, ‘You are Asian, boy! Why muddy that? Why not seek after something truly Asian, not diluted by a westerner’s ravings?’ Don’t worry, Doctor; I recoil just as much on recalling that memory as you do on hearing it! Can you believe I thought such a thing? Of Van Gogh of all people? But alas I did. If it was not for Petrus I would have said to the young Viet that we Japanese were fighting a war to keep Asia for its own, sure to remind Trau that if the Kenpeitai were to hear him, they would charge him with sedition.

It was Petrus who gave voice to my doubts.

‘What is there to like about the countryside?’ He questioned from over his coffee cup. ‘The cutthroats? The revolutionaries? Disease? The fields filled with centuries of shit?’

For the first time that morning, I heard Kieu speak. ‘I like the rice fields,’ she said, her French accent soft, as if she were from the Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur. ‘The sky, the way it hangs on them – or, just before harvest, the passing of a breeze through the long green stalks: it reminds me of ripples crossing a temple pond.’

‘Only at a distance,’ Petrus countered. ‘Up close, those stalks look more like the fur of a mangy dog. The smell is worse still. The route de Bing Bông is a tourniquet. The road keeps disease at bay.’

Kieu excused herself in her native tongue and joined Kozu at the water’s edge. I watched them both, very much aware that, out of the corner of his eye, Petrus was watching me. How lightly the Viet girl walked, Doctor. How often she smiled, when talking with the old artist. I wondered what they could be speaking of. I can recall lamenting, in that moment, the fact that Kozu no longer painted women’s portraits. After his first expeditions to the China front in ’38, the military censors had deemed his Asian nudes decadent. ‘Ours is a holy war,’ one critic had written soon afterwards. ‘Who would choose the bark of even the smoothest tree, if it meant neglecting its blossoms?’

During dinner on March 9th, a week after my arrival in Saigon, General Tsuchihashi, the commander of Japanese forces in Indochina, slipped away from a reception he was holding for a number of French diplomats and administrators, at his residence in the centre of Saigon. At 7.00 pm, the General issued his French counterpart, General Decoux an ultimatum: secede Indochina, or face forced disarmament. Preparations had already been made, ammunition distributed. Decoux stalled for time. He was granted two hours. Not all Japanese units, on alert since the previous night, waited for the two hours to play out. They went on the offensive. Taking advantage of the pockets of chaos that followed, I accompanied Honma and his men, as they rounded up suspected members of the Free French, their sympathizers and métis, Eurasian members of the Sûreté. I took my list and annexed those artworks at greatest risk of damage if full scale insurrection were to erupt. We encountered little resistance. At around 9.00 pm, I remember, there was burst of automatic weapons fire, somewhere close to the military hospital, then silence.

It sounds extraordinary to tell you now, Doctor, but I had completed my work by late afternoon of the following day, Honma’s men were so efficient. I returned to Cholon without sleeping, where I deposited the works I had liberated from the villas of the French Quarter, the Governor General’s office and home in particular (one detachment of Honma’s men even struck out for the Ville Blanche, the governor’s residence on the coast). Japanese units were visible on the streets, their smiling young men (those who had never seen action before) a stark contrast to the weathered faces of their older colleagues, those who were supposed to be recuperating after action in Burma. Sound-trucks travelled the streets, sporting the flags and slogans of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, passing under many billboards still carrying the images of Marshal Pétain. Local civilians stayed in their houses.

Once, during the night, and again at first light, the major dispatched runners to check on Kozu’s so-called Yellow House in Cholon. A company of French soldiers had escaped the city via the route de Bing Bông during the night and faded into the paddies beyond. My work complete, I ensured the major I would go to the artist myself. The operation of the previous night seemed to have invigorated the major and he talked to me excitedly about some of the pieces I had acquired. Still he smoked his cigarettes in his affected manner, but his tone of voice had softened, so that I started to feel a sense of camaraderie well up between us.

‘Tell Kozu, I now have sufficient materials to at least start on my painting,’ the major said, as I took my leave. ‘The artist should be moving onto other projects by now. You should both come out to the Hippodrome this afternoon.’

There it was, Doctor. An invitation I paid little attention to, seeing that I did not really follow the major’s meaning. That invitation has landed me here, in this old house, living in fear of the Americans, of their interest in me and my grandfather’s gallery, exiled as I am to these mountains, to a life of millet gruel and vegetables I pull from the soil with my bare hands. And the snows will settle here soon. What will I do then? Your painting is more dangerous to me than you can imagine. At the time, I gave little thought to the major’s enigmatic words. I don’t think I even questioned what he meant by materials. Honma was a major in the Kenpeitai, as I’ve already said. It was best to obey. It was safer. More settling.

I found Kozu asleep on the bed tucked away in his studio, but before I could rouse him, Trau shouted up from the foyer. The boy was almost dancing with happiness.

‘We are free,’ he gushed. ‘The French have been swept aside! This is no longer Indochine, but a new country, an ancient one: welcome, M. Takayanagi, to Vietnamien.’

I asked after Petrus. A rich Chinaman like him was to be watched at such a delicate time. But Trau was too preoccupied to take my questions seriously. With great élan, he revealed to me his latest works, three paintings he had worked on throughout the night – one after the other, after the other– and into the morning. All three were of the countryside directly across from the villa, their paint wet and fields gouged out of chartreuse and pear green.

When Kozu came to, I informed him of Honma’s message. He looked uncertain and out of cheer, Doctor. Quite out of character. Trau showed him those same three paintings of his, but the master artist was unable to say a single word of praise. He did not even grace the young Viet’s efforts with a smile.

He said that he must hurry; that Trau must help him complete his portrait of the liberating soldier. What with the coup, the painting was of vital importance, more now than ever. While he mixed his paints and prepared his palette, he explained to both Trau and I that your tableau, Doctor, had been commissioned by the Army: that the grand image was to act as a means of justifying the military action that had swept the French from administrative power. It would be taken most probably to the Hotel de Ville. There, in that grand foyer it would proclaim our conquering army a force of liberation.

I saw through him. Honma, surely, was looking to collect on whatever agreement they had made. The major wanted his portrait completed. The privileges and freedoms granted Kozu by the major came with a price. Still, the master artist could not abandon your painting Doctor.

How long had I spent watching Kozu during my spare hours? How much longer still did I look on the artist’s efforts to lift Trau and Petrus’ forms from the mist of its burnt-sienna under paint, along with the walls and floors and furniture of the Yellow House? How long did Kozu agonize over Kieu’s bound body? It is hard to say. There the canvas lay, your painting Doctor, on the floor of the studio, an expression of our struggle against western imperialism. Kozu was bent over Trau’s figure, shuffling round the edge of the image so as to focus on the grain of a cabinet, all the time instructing the young Viet on where to work up an edge of curtain, a fold in his own painted uniform, a crease in his sister’s smock. For that past week, the painting had been a symbol to me, g

rand and beautiful, but somehow strangely abstract. Overnight, its metaphors had turned to flesh.

Trau saw it too and quickly dropped the subject of his own paintings, those three brightly coloured and empty landscapes, which he left to dry on the balcony. Every word, every instruction Kozu issued the young Viet, looked to penetrate Trau to the core. He revelled in the oils that gradually coated his fingers, then the whole of his hands. At one point, Kozu ordered him to dress once again into his corporal’s uniform, after which the artist ordered the boy to stand, to burst through the balcony window curtains, to pause, telling him to keep his back erect, legs slightly bent, face stern, proud. An hour later, his corporal’s uniform dark with sweat in the late afternoon heat, Trau once again fell to his knees, taking up fresh brushes, and following Kozu instructions with renewed vigour.

Wagner blared in the background: the grand march from the German’s Tannhäuser. That favourite of Van Gogh’s.

Petrus, by that time had returned from whatever errand had taken him into the city. He came to the studio, looking for his wife. Kozu told him to take up his usual position at Trau’s feet. The Chinaman refused. Kozu lost his temper and informed his host what would happen to him if he failed to cooperate. Once installed at Trau’s feet, en pose, Petrus chain-smoked one Golden Bat cigarette after another, until his head finally slumped down onto the floorboards. Until that moment, Kozu kept me busy by barking orders at me. ‘Open that tin of turpentine; wash out these brushes; open the curtains wider; fetch us a lamp, the light is fading too quickly; Trau needs a glass of water.’ And the like. But with Petrus unconscious on the floor, Kozu’s mood shifted.

‘Fetch Kieu,’ he said.

I found the girl in the garden, pacing the canal bank, dressed in a cotton blouse – yes, it was yellow, with a mandarin neck. Her hair was up. What details to remember Doctor! I had grown so accustomed to watching her pose for Kozu in that black peasant’s smock he had found her that I had forgotten she was the wife of the wealthy businessman. I informed her of Kozu’s request, of how urgently she was needed.

‘You are the body of Asia lost,’ Kozu said to the girl in the studio as he bound her hands, his voice strained. ‘Lost: then saved, by the heroic coming of we Japanese.’

Kozu and Trau painted well into the evening.

Perhaps the raid that levelled part of the Chinese City that night was in reprisal for our military’s success – our last success, as it was to prove to be. A token, Doctor, a means to let us know we were surrounded. The bombers arced round into Saigon from the southeast. Kozu and I were sitting in the garden of the Yellow House when they came. A siren pierced the sky and a strange stillness fell over the garden, along the canal, and those tufts of jungle that crept up to the water’s edge past the distillery, where the palms gazed down at their own reflections. The insects and frogs in the paddies fell silent, too. I stared at the black sheen covering the canal, that oily surface, whose darkness seemed to spread out from the filthy membrane to ooze over the boats and banks and leaves and walls and of the city.

The drone of heavy engines rose out from that silence, as if the planes were spectral, a plague of ghosts gathering for vengeance above the Plain of Reeds. I will reiterate Doctor: it was a night raid. An unusual tactic for the whites by that time in the war, seeing we no longer had any fighters with which to counter them. All of that fuel Petrus’ plant distilled and none of it could save the city of his birth.

I believe I said to Kozu something about the locals, how I imagined them smiling up at the enemy aircraft with those vacant Asian smiles of theirs, neither happy, nor angry, but just because the foreigners were there, over their country. How could I have known that only two days before, on the eve of our great coup in Indochina, American bombers had dropped petroleum jelly and incendiaries on Tokyo; that they had turned the city to ash, my grandfather’s gallery included? It would take weeks for such a truth to become known to me.

‘You’re drunk,’ was the artist’s reply.

‘No more than you.’

On the other side of Arroyo Chinois, an anti-aircraft battery opened up. A melancholy sound. It all seemed so ridiculous, those shells bursting amongst the stars, bringing to mind thoughts of summer fireworks over the Sumida River back home. I told Kozu we should probably find a shelter. Did the house have a cellar? I was not too concerned at that point, believing as I did, that the planes would strike at the docks on the far eastern side of the city.

Kozu turned his shoulders and looked back into the house through the latticed wall. A dimmed lantern burned inside, on a bureau angled obliquely into a corner of the parlour, its orange ball made invisible to anyone on the other side of the canal. There Petrus sat, opium-dazed, writing what he called, ‘an epic poem.’ An hour had passed since the Chinaman stirred from his drugged sleep and found his wife kneeling before Kozu, her hands bound behind her back, smiling at the painter. On seeing Petrus awake, Kozu had backed away from his canvas and told Trau to change out of his uniform, to wash his hands. Whatever spell the girl cast over the artist when she modelled for him was broken. He would not lay down another stroke that night, he said. Besides he had decided that gold leaf was better for the bayonet of Trau’s rifle. The process of digging down into his layers of paint, to strip away that slither of gunmetal and clean the oil off the canvas was too intricate a task to attempt at night. And where was he to lay his hands on such a precious material? There was no choice but to wait for daylight. Moreover, he was exhausted. The job of preparing and applying the bole was beyond him for the time being, whether he could find any gold or not. The adhesive, too, would take an age to dry enough to become sticky, for the gold to be applied.

The lantern cast shadows inside the Chinaman’s hollow cheeks. Its light welled in the deep polish of the desk’s mahogany, like something from Van Gogh’s Night Cafe.

Kieu was somewhere in the parlour, close to her husband and out of sight of us. I could feel her presence. I could almost hear her breathe, or so I thought. Most probably she was right behind Kozu, a dark shape filling so few holes of the lattice work. But she was listening to every word we said, of that I was sure. Listening. Waiting for us to move to safety. Kozu was tense, but remained in his chair, as if he too felt the girl’s eyes and ears. He wanted to impress her.

The sirens cried on. The air defences putted and pom-pom’ed. Every surface sweated. My clothes were damp, as always, and there was no hope of relief. The first bombs whistled down and exploded. From the veranda, I looked out through the trees of the garden and watched the amber glow of conflagration thicken amongst the warehouses to the east, then the north. The bombs were a good ways off, but, still, they fell on Cholon. This was not to be a raid on the Docks de Saigon, after all. Frantic voices erupted from the distillery’s complex. The wood decking beneath my feet vibrated. Shocked into waves, the canal’s surface lapped the pilings like netted fish.

Kieu slipped out of the darkness and stood beside us, her back to the canal. Her eyes were wide and bright against her dark face. Kozu stirred. His measured movements exuded confidence, his very silence inspiring calm.

We made our way through the parlour, Kozu leading Kieu by the elbow. Dipping his pen into the inkwell, Petrus refused to look up at us, to acknowledge our passing. Trau met us in the hall, fretting over the fate of Kozu’s painting and not his own.

‘It’s still wet,’ the boy said again and again. It was as much as we could do to stop him running up the stairwell and to the studio. ‘Are you just going to abandon it?’ he raged, but his sister calmed him.

Outside the rumble of the bombs became a roar. A strange wind whipped up and around us. The air quaked. I stumbled about because my legs were shaking and the ground heaved. I cursed the dyke and its road, the white gravel that was as good as a lit boulevard, a neon strip leading the bombers along the canal to the distillery. The earth swallowed us. A slit trench, Doctor, dug by the men of the distillery. Local voices babbled up and down that wrinkle in the earth. I taste

d the damp soil on my lips.

A hundred yards away, a warehouse flew to splitters, then another behind it, in the opposite direction to the Yellow House. A barge on the canal exploded. Warm water fell on us like soft rain. White smoke, Doctor. The stink of cordite. All this I remember with vivid intensity. The flashes of light. Kozu, with his lips pressed into Kieu’s hair. Shockwaves. Shrapnel – not quite splitting the air at that distance, but falling none the less.

Something struck me on the head, right on the crown, like a nut falling from a tree. I wondered what it could have been, where it had come from. Can you imagine, Doctor? The bombs were falling closer and closer and a strange curiosity took over me. Was its part of a rivet from the boat? Or the tip of a nail wrenched free from a roof beam? My fingers sifted through the soil in the bottom of the trench, around Kozu and Kieu’s knees. And there I found it, Doctor. Human teeth. A fragment of a person’s overbite.

Honma arrived the next morning and I accompanied the major on an inspection of the warehouses close to the distillery. The shock of having survived the attack was wet within my nerves, like the paint on Trau’s canvases. I could not stop babbling.

‘This reminds me of Ginza after the Earthquake of ’23,’ I said at one point. ‘I recognize the stench. It’s like rotten apricots.’

Kozu had already taken Kieu back to the villa, leaving Trau to wander through the debris, to stare at the coolies, gathered from the local warehouses, who were laying out the bodies of those killed in the raid. Military policemen paced up and down the route de Bing Bông, handkerchiefs wrapped around their faces. Over a megaphone a voice boomed out through the smoke. I asked Honma what it was saying.

‘Look at what the imperialists inflict upon your people; that is what it says.’

The thought of those teeth kept coming back to me, their texture haunting my fingertips, as I played with their cloth bundle in my pocket. How fallible the body was. How easily something like a tooth, even a jaw, could be lost, blown loose by an explosion. It was not something I had thought much about before. Eyes, yes. And fingers.

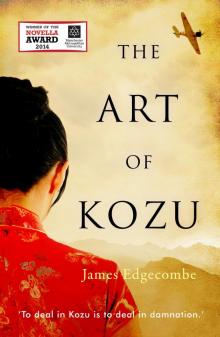

The Art of Kozu

The Art of Kozu